Archimedes Circle Area Proof - Inscribed Polygons on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Archimedes of Syracuse (;; ) was a

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

mathematician

A mathematician is someone who uses an extensive knowledge of mathematics in their work, typically to solve mathematical problems.

Mathematicians are concerned with numbers, data, quantity, structure, space, models, and change.

History

On ...

, physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe.

Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate cau ...

, engineer

Engineers, as practitioners of engineering, are professionals who Invention, invent, design, analyze, build and test machines, complex systems, structures, gadgets and materials to fulfill functional objectives and requirements while considerin ...

, astronomer

An astronomer is a scientist in the field of astronomy who focuses their studies on a specific question or field outside the scope of Earth. They observe astronomical objects such as stars, planets, moons, comets and galaxies – in either ...

, and inventor

An invention is a unique or novel device, method, composition, idea or process. An invention may be an improvement upon a machine, product, or process for increasing efficiency or lowering cost. It may also be an entirely new concept. If an ...

from the ancient city of Syracuse

Syracuse may refer to:

Places Italy

* Syracuse, Sicily, or spelled as ''Siracusa''

* Province of Syracuse

United States

*Syracuse, New York

**East Syracuse, New York

** North Syracuse, New York

* Syracuse, Indiana

*Syracuse, Kansas

*Syracuse, M ...

in Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

. Although few details of his life are known, he is regarded as one of the leading scientists in classical antiquity

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ...

. Considered the greatest mathematician of ancient history

Ancient history is a time period from the beginning of writing and recorded human history to as far as late antiquity. The span of recorded history is roughly 5,000 years, beginning with the Sumerian cuneiform script. Ancient history cove ...

, and one of the greatest of all time,*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

* Archimedes anticipated modern calculus

Calculus, originally called infinitesimal calculus or "the calculus of infinitesimals", is the mathematics, mathematical study of continuous change, in the same way that geometry is the study of shape, and algebra is the study of generalizati ...

and analysis

Analysis ( : analyses) is the process of breaking a complex topic or substance into smaller parts in order to gain a better understanding of it. The technique has been applied in the study of mathematics and logic since before Aristotle (3 ...

by applying the concept of the infinitely small and the method of exhaustion

The method of exhaustion (; ) is a method of finding the area of a shape by inscribing inside it a sequence of polygons whose areas converge to the area of the containing shape. If the sequence is correctly constructed, the difference in are ...

to derive and rigorously prove a range of geometrical

Geometry (; ) is, with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. It is concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. A mathematician who works in the field of geometry is c ...

theorem

In mathematics, a theorem is a statement that has been proved, or can be proved. The ''proof'' of a theorem is a logical argument that uses the inference rules of a deductive system to establish that the theorem is a logical consequence of t ...

s. These include the area of a circle

In geometry, the area enclosed by a circle of radius is . Here the Greek letter represents the constant ratio of the circumference of any circle to its diameter, approximately equal to 3.14159.

One method of deriving this formula, which ori ...

, the surface area

The surface area of a solid object is a measure of the total area that the surface of the object occupies. The mathematical definition of surface area in the presence of curved surfaces is considerably more involved than the definition of ...

and volume

Volume is a measure of occupied three-dimensional space. It is often quantified numerically using SI derived units (such as the cubic metre and litre) or by various imperial or US customary units (such as the gallon, quart, cubic inch). ...

of a sphere

A sphere () is a geometrical object that is a three-dimensional analogue to a two-dimensional circle. A sphere is the set of points that are all at the same distance from a given point in three-dimensional space.. That given point is the c ...

, the area of an ellipse

In mathematics, an ellipse is a plane curve surrounding two focal points, such that for all points on the curve, the sum of the two distances to the focal points is a constant. It generalizes a circle, which is the special type of ellipse in ...

, the area under a parabola

In mathematics, a parabola is a plane curve which is mirror-symmetrical and is approximately U-shaped. It fits several superficially different mathematical descriptions, which can all be proved to define exactly the same curves.

One descri ...

, the volume of a segment of a paraboloid of revolution, the volume of a segment of a hyperboloid of revolution

In geometry, a hyperboloid of revolution, sometimes called a circular hyperboloid, is the surface generated by rotating a hyperbola around one of its principal axes. A hyperboloid is the surface obtained from a hyperboloid of revolution by def ...

, and the area of a spiral

In mathematics, a spiral is a curve which emanates from a point, moving farther away as it revolves around the point.

Helices

Two major definitions of "spiral" in the American Heritage Dictionary are: Heath, Thomas L. 1897. ''Works of Archimedes''.

Archimedes' other mathematical achievements include deriving an approximation of pi, defining and investigating the

Archimedes was born c. 287 BC in the seaport city of

Archimedes was born c. 287 BC in the seaport city of

A large part of Archimedes' work in engineering probably arose from fulfilling the needs of his home city of

A large part of Archimedes' work in engineering probably arose from fulfilling the needs of his home city of

Archimedes may have used mirrors acting collectively as a

Archimedes may have used mirrors acting collectively as a

Archimedes was able to use indivisibles (a precursor to

Archimedes was able to use indivisibles (a precursor to

In ''

In ''

The works of Archimedes were written in

The works of Archimedes were written in

In this two-volume treatise addressed to Dositheus, Archimedes obtains the result of which he was most proud, namely the relationship between a

In this two-volume treatise addressed to Dositheus, Archimedes obtains the result of which he was most proud, namely the relationship between a

Also known as Loculus of Archimedes or Archimedes' Box, this is a

Also known as Loculus of Archimedes or Archimedes' Box, this is a

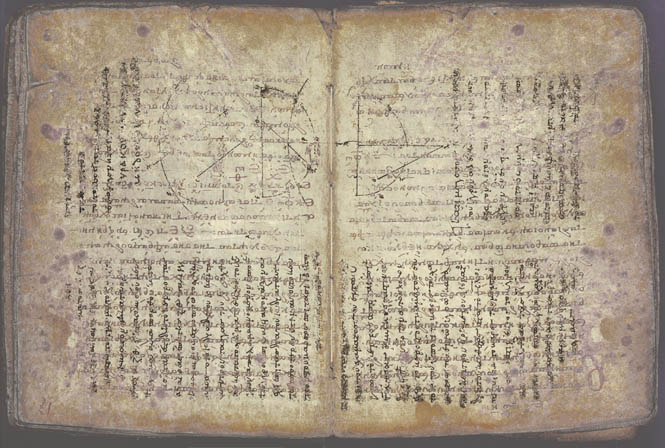

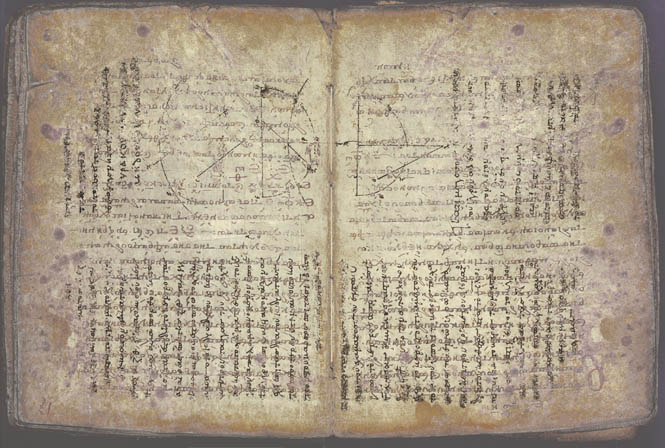

The foremost document containing Archimedes' work is the Archimedes Palimpsest. In 1906, the Danish professor Johan Ludvig Heiberg visited

The foremost document containing Archimedes' work is the Archimedes Palimpsest. In 1906, the Danish professor Johan Ludvig Heiberg visited

Historians of science and mathematics almost universally agree that Archimedes was the finest mathematician from antiquity.

Historians of science and mathematics almost universally agree that Archimedes was the finest mathematician from antiquity.

Archimedean spiral

The Archimedean spiral (also known as the arithmetic spiral) is a spiral named after the 3rd-century BC Greek mathematician Archimedes. It is the locus corresponding to the locations over time of a point moving away from a fixed point with a ...

, and devising a system using exponentiation

Exponentiation is a mathematical operation, written as , involving two numbers, the '' base'' and the ''exponent'' or ''power'' , and pronounced as " (raised) to the (power of) ". When is a positive integer, exponentiation corresponds to ...

for expressing very large numbers

Large numbers are numbers significantly larger than those typically used in everyday life (for instance in simple counting or in monetary transactions), appearing frequently in fields such as mathematics, cosmology, cryptography, and statistical ...

. He was also one of the first to apply mathematics to physical phenomena

Physical may refer to:

*Physical examination

In a physical examination, medical examination, or clinical examination, a medical practitioner examines a patient for any possible medical signs or symptoms of a medical condition. It generally cons ...

, founding hydrostatics

Fluid statics or hydrostatics is the branch of fluid mechanics that studies the condition of the equilibrium of a floating body and submerged body "fluids at hydrostatic equilibrium and the pressure in a fluid, or exerted by a fluid, on an imme ...

and statics

Statics is the branch of classical mechanics that is concerned with the analysis of force and torque (also called moment) acting on physical systems that do not experience an acceleration (''a''=0), but rather, are in static equilibrium with ...

. Archimedes' achievements in this area include a proof of the principle of the lever

A lever is a simple machine consisting of a beam or rigid rod pivoted at a fixed hinge, or '' fulcrum''. A lever is a rigid body capable of rotating on a point on itself. On the basis of the locations of fulcrum, load and effort, the lever is d ...

, the widespread use of the concept of center of gravity

In physics, the center of mass of a distribution of mass in space (sometimes referred to as the balance point) is the unique point where the weighted relative position of the distributed mass sums to zero. This is the point to which a force ma ...

, and the enunciation of the law of buoyancy. He is also credited with designing innovative machine

A machine is a physical system using power to apply forces and control movement to perform an action. The term is commonly applied to artificial devices, such as those employing engines or motors, but also to natural biological macromolecul ...

s, such as his screw pump

A screw pump is a positive-displacement pump that use one or several screws to move fluid solids or liquids along the screw(s) axis.

Three principal forms exist; In its simplest form (the Archimedes' screw pump or 'water screw'), a single sc ...

, compound pulleys, and defensive war machines to protect his native Syracuse

Syracuse may refer to:

Places Italy

* Syracuse, Sicily, or spelled as ''Siracusa''

* Province of Syracuse

United States

*Syracuse, New York

**East Syracuse, New York

** North Syracuse, New York

* Syracuse, Indiana

*Syracuse, Kansas

*Syracuse, M ...

from invasion.

Archimedes died during the siege of Syracuse, when he was killed by a Roman soldier despite orders that he should not be harmed. Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the esta ...

describes visiting Archimedes' tomb, which was surmounted by a sphere

A sphere () is a geometrical object that is a three-dimensional analogue to a two-dimensional circle. A sphere is the set of points that are all at the same distance from a given point in three-dimensional space.. That given point is the c ...

and a cylinder

A cylinder (from ) has traditionally been a three-dimensional solid, one of the most basic of curvilinear geometric shapes. In elementary geometry, it is considered a prism with a circle as its base.

A cylinder may also be defined as an ...

that Archimedes requested be placed there to represent his mathematical discoveries.

Unlike his inventions, Archimedes' mathematical writings were little known in antiquity. Mathematicians from Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

read and quoted him, but the first comprehensive compilation was not made until by Isidore of Miletus

Isidore of Miletus ( el, Ἰσίδωρος ὁ Μιλήσιος; Medieval Greek pronunciation: ; la, Isidorus Miletus) was one of the two main Byzantine Greek architects (Anthemius of Tralles was the other) that Emperor Justinian I commissioned ...

in Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

, while commentaries on the works of Archimedes by Eutocius

Eutocius of Ascalon (; el, Εὐτόκιος ὁ Ἀσκαλωνίτης; 480s – 520s) was a Palestinian-Greek mathematician who wrote commentaries on several Archimedean treatises and on the Apollonian ''Conics''.

Life and work

Little is ...

in the 6th century opened them to wider readership for the first time. The relatively few copies of Archimedes' written work that survived through the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

were an influential source of ideas for scientists during the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

and again in the 17th century, while the discovery in 1906 of previously lost works by Archimedes in the Archimedes Palimpsest

The Archimedes Palimpsest is a parchment codex palimpsest, originally a Byzantine Greek copy of a compilation of Archimedes and other authors. It contains two works of Archimedes that were thought to have been lost (the '' Ostomachion'' and ...

has provided new insights into how he obtained mathematical results.

Biography

Archimedes was born c. 287 BC in the seaport city of

Archimedes was born c. 287 BC in the seaport city of Syracuse

Syracuse may refer to:

Places Italy

* Syracuse, Sicily, or spelled as ''Siracusa''

* Province of Syracuse

United States

*Syracuse, New York

**East Syracuse, New York

** North Syracuse, New York

* Syracuse, Indiana

*Syracuse, Kansas

*Syracuse, M ...

, Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

, at that time a self-governing colony in Magna Graecia

Magna Graecia (, ; , , grc, Μεγάλη Ἑλλάς, ', it, Magna Grecia) was the name given by the Romans to the coastal areas of Southern Italy in the present-day Italian regions of Calabria, Apulia, Basilicata, Campania and Sicily; the ...

. The date of birth is based on a statement by the Byzantine Greek historian John Tzetzes

John Tzetzes ( grc-gre, Ἰωάννης Τζέτζης, Iōánnēs Tzétzēs; c. 1110, Constantinople – 1180, Constantinople) was a Byzantine poet and grammarian who is known to have lived at Constantinople in the 12th century.

He was able to pr ...

that Archimedes lived for 75 years before his death in 212 BC. In the '' Sand-Reckoner'', Archimedes gives his father's name as Phidias, an astronomer about whom nothing else is known. A biography of Archimedes was written by his friend Heracleides, but this work has been lost, leaving the details of his life obscure. It is unknown, for instance, whether he ever married or had children, or if he ever visited Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

, Egypt, during his youth. From his surviving written works, it is clear that he maintained collegiate relations with scholars based there, including his friend Conon of Samos

Conon of Samos ( el, Κόνων ὁ Σάμιος, ''Konōn ho Samios''; c. 280 – c. 220 BC) was a Greek astronomer and mathematician. He is primarily remembered for naming the constellation Coma Berenices.

Life and work

Conon was born on Sam ...

and the head librarian Eratosthenes of Cyrene

Eratosthenes of Cyrene (; grc-gre, Ἐρατοσθένης ; – ) was a Greek polymath: a mathematician, geographer, poet, astronomer, and music theorist. He was a man of learning, becoming the chief librarian at the Library of Alexandria ...

.In the preface to ''On Spirals'' addressed to Dositheus of Pelusium, Archimedes says that "many years have elapsed since Conon's death." Conon of Samos

Conon of Samos ( el, Κόνων ὁ Σάμιος, ''Konōn ho Samios''; c. 280 – c. 220 BC) was a Greek astronomer and mathematician. He is primarily remembered for naming the constellation Coma Berenices.

Life and work

Conon was born on Sam ...

lived c. 280–220 BC, suggesting that Archimedes may have been an older man when writing some of his works.

The standard versions of Archimedes' life were written long after his death by Greek and Roman historians. The earliest reference to Archimedes occurs in '' The Histories'' by Polybius

Polybius (; grc-gre, Πολύβιος, ; ) was a Greek historian of the Hellenistic period. He is noted for his work , which covered the period of 264–146 BC and the Punic Wars in detail.

Polybius is important for his analysis of the mixed ...

( 200–118 BC), written about 70 years after his death. It sheds little light on Archimedes as a person, and focuses on the war machines that he is said to have built in order to defend the city from the Romans. Polybius remarks how, during the Second Punic War

The Second Punic War (218 to 201 BC) was the second of three wars fought between Carthage and Rome, the two main powers of the western Mediterranean in the 3rd century BC. For 17 years the two states struggled for supremacy, primarily in Ital ...

, Syracuse switched allegiances from Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

to Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classi ...

, resulting in a military campaign to take the city under the command of Marcus Claudius Marcellus

Marcus Claudius Marcellus (; 270 – 208 BC), five times elected as consul of the Roman Republic, was an important Roman military leader during the Gallic War of 225 BC and the Second Punic War. Marcellus gained the most prestigious award a Roma ...

and Appius Claudius Pulcher, which lasted from 213 to 212 BC. He notes that the Romans underestimated Syracuse's defenses, and mentions several machines Archimedes designed, including improved catapults, cranelike machines that could be swung around in an arc, and stone-throwers. Although the Romans ultimately captured the city, they suffered considerable losses due to Archimedes' inventiveness.

Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the esta ...

(106–43 BC) mentions Archimedes in some of his works. While serving as a quaestor

A ( , , ; "investigator") was a public official in Ancient Rome. There were various types of quaestors, with the title used to describe greatly different offices at different times.

In the Roman Republic, quaestors were elected officials who ...

in Sicily, Cicero found what was presumed to be Archimedes' tomb near the Agrigentine gate in Syracuse, in a neglected condition and overgrown with bushes. Cicero had the tomb cleaned up and was able to see the carving and read some of the verses that had been added as an inscription. The tomb carried a sculpture illustrating Archimedes' favorite mathematical proof, that the volume and surface area of the sphere are two-thirds that of the cylinder including its bases. He also mentions that Marcellus brought to Rome two planetariums Archimedes built. The Roman historian Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding in ...

(59 BC–17 AD) retells Polybius' story of the capture of Syracuse and Archimedes' role in it.

Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for hi ...

(45–119 AD) wrote in his ''Parallel Lives

Plutarch's ''Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans'', commonly called ''Parallel Lives'' or ''Plutarch's Lives'', is a series of 48 biographies of famous men, arranged in pairs to illuminate their common moral virtues or failings, probably writt ...

'' that Archimedes was related to King Hiero II

Hiero II ( el, Ἱέρων Β΄; c. 308 BC – 215 BC) was the Greek tyrant of Syracuse from 275 to 215 BC, and the illegitimate son of a Syracusan noble, Hierocles, who claimed descent from Gelon. He was a former general of Pyrrhus of Epirus an ...

, the ruler of Syracuse. He also provides at least two accounts on how Archimedes died after the city was taken. According to the most popular account, Archimedes was contemplating a mathematical diagram when the city was captured. A Roman soldier commanded him to come and meet Marcellus, but he declined, saying that he had to finish working on the problem. This enraged the soldier, who killed Archimedes with his sword. Another story has Archimedes carrying mathematical instruments before being killed because a soldier thought they were valuable items. Marcellus was reportedly angered by Archimedes' death, as he considered him a valuable scientific asset (he called Archimedes "a geometrical Briareus

In Greek mythology, the Hecatoncheires ( grc-gre, Ἑκατόγχειρες, , Hundred-Handed Ones), or Hundred-Handers, also called the Centimanes, (; la, Centimani), named Cottus, Briareus (or Aegaeon) and Gyges (or Gyes), were three monstrous ...

") and had ordered that he should not be harmed.

The last words attributed to Archimedes are "Do not disturb my circles

"''Nōlī turbāre circulōs meōs!''" is a Latin phrase, meaning "Do not disturb my circles!". It is said to have been uttered by Archimedes—in reference to a geometric figure he had outlined on the sand—when he was confronted by a Roman sold ...

" (Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

, "''Noli turbare circulos meos''"; Katharevousa Greek, "μὴ μου τοὺς κύκλους τάραττε"), a reference to the mathematical drawing that he was supposedly studying when disturbed by the Roman soldier. There is no reliable evidence that Archimedes uttered these words and they do not appear in Plutarch's account. A similar quotation is found in the work of Valerius Maximus

Valerius Maximus () was a 1st-century Latin writer and author of a collection of historical anecdotes: ''Factorum ac dictorum memorabilium libri IX'' ("Nine books of memorable deeds and sayings", also known as ''De factis dictisque memorabilibus'' ...

(fl. 30 AD), who wrote in ''Memorable Doings and Sayings'', "" ("... but protecting the dust with his hands, said 'I beg of you, do not disturb this).

Discoveries and inventions

Archimedes' principle

The most widely known anecdote about Archimedes tells of how he invented a method for determining the volume of an object with an irregular shape. According toVitruvius

Vitruvius (; c. 80–70 BC – after c. 15 BC) was a Roman architect and engineer during the 1st century BC, known for his multi-volume work entitled '' De architectura''. He originated the idea that all buildings should have three attribut ...

, a votive crown

A votive crown is a votive offering in the form of a crown, normally in precious metals and often adorned with jewels. Especially in the Early Middle Ages, they are of a special form, designed to be suspended by chains at an altar, shrine or im ...

for a temple had been made for King Hiero II of Syracuse, who had supplied the pure gold to be used; Archimedes was asked to determine whether some silver had been substituted by the dishonest goldsmith. Archimedes had to solve the problem without damaging the crown, so he could not melt it down into a regularly shaped body in order to calculate its density

Density (volumetric mass density or specific mass) is the substance's mass per unit of volume. The symbol most often used for density is ''ρ'' (the lower case Greek letter rho), although the Latin letter ''D'' can also be used. Mathematicall ...

.

In Vitruvius' account, Archimedes noticed while taking a bath that the level of the water in the tub rose as he got in, and realized that this effect could be used to determine the crown's volume

Volume is a measure of occupied three-dimensional space. It is often quantified numerically using SI derived units (such as the cubic metre and litre) or by various imperial or US customary units (such as the gallon, quart, cubic inch). ...

. For practical purposes water is incompressible, so the submerged crown would displace an amount of water equal to its own volume. By dividing the mass of the crown by the volume of water displaced, the density of the crown could be obtained. This density would be lower than that of gold if cheaper and less dense metals had been added. Archimedes then took to the streets naked, so excited by his discovery that he had forgotten to dress, crying "Eureka

Eureka (often abbreviated as E!, or Σ!) is an intergovernmental organisation for research and development funding and coordination. Eureka is an open platform for international cooperation in innovation. Organisations and companies applying th ...

!" ( el, "εὕρηκα, ''heúrēka''!, ). The test on the crown was conducted successfully, proving that silver had indeed been mixed in.

The story of the golden crown does not appear anywhere in Archimedes' known works. The practicality of the method it describes has been called into question due to the extreme accuracy that would be required while measuring the water displacement. Archimedes may have instead sought a solution that applied the principle known in hydrostatics

Fluid statics or hydrostatics is the branch of fluid mechanics that studies the condition of the equilibrium of a floating body and submerged body "fluids at hydrostatic equilibrium and the pressure in a fluid, or exerted by a fluid, on an imme ...

as Archimedes' principle

Archimedes' principle (also spelled Archimedes's principle) states that the upward buoyant force that is exerted on a body immersed in a fluid, whether fully or partially, is equal to the weight of the fluid that the body displaces. Archimedes' ...

, which he describes in his treatise ''On Floating Bodies

''On Floating Bodies'' ( el, Περὶ τῶν ἐπιπλεόντων σωμάτων) is a Greek-language work consisting of two books written by Archimedes of Syracuse (287 – c. 212 BC), one of the most important mathematicians, physicis ...

''. This principle states that a body immersed in a fluid experiences a buoyant force

Buoyancy (), or upthrust, is an upward force exerted by a fluid that opposes the weight of a partially or fully immersed object. In a column of fluid, pressure increases with depth as a result of the weight of the overlying fluid. Thus the pr ...

equal to the weight of the fluid it displaces. Using this principle, it would have been possible to compare the density of the crown to that of pure gold by balancing the crown on a scale with a pure gold reference sample of the same weight, then immersing the apparatus in water. The difference in density between the two samples would cause the scale to tip accordingly. Galileo Galilei

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642) was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a polymath. Commonly referred to as Galileo, his name was pronounced (, ). He ...

, who in 1586 invented a hydrostatic balance for weighing metals in air and water inspired by the work of Archimedes, considered it "probable that this method is the same that Archimedes followed, since, besides being very accurate, it is based on demonstrations found by Archimedes himself."

Archimedes' screw

A large part of Archimedes' work in engineering probably arose from fulfilling the needs of his home city of

A large part of Archimedes' work in engineering probably arose from fulfilling the needs of his home city of Syracuse

Syracuse may refer to:

Places Italy

* Syracuse, Sicily, or spelled as ''Siracusa''

* Province of Syracuse

United States

*Syracuse, New York

**East Syracuse, New York

** North Syracuse, New York

* Syracuse, Indiana

*Syracuse, Kansas

*Syracuse, M ...

. The Greek writer Athenaeus of Naucratis

Athenaeus of Naucratis (; grc, Ἀθήναιος ὁ Nαυκρατίτης or Nαυκράτιος, ''Athēnaios Naukratitēs'' or ''Naukratios''; la, Athenaeus Naucratita) was a Greek rhetorician and grammarian, flourishing about the end of th ...

described how King Hiero II commissioned Archimedes to design a huge ship, the ''Syracusia

''Syracusia'' ( el, Συρακουσία, ''syrakousía'', literally "of Syracuse") was an ancient Greek ship sometimes claimed to be the largest transport ship of antiquity. She was reportedly too big for any port in Sicily, and thus only sailed ...

'', which could be used for luxury travel, carrying supplies, and as a naval warship

A naval ship is a military ship (or sometimes boat, depending on classification) used by a navy. Naval ships are differentiated from civilian ships by construction and purpose. Generally, naval ships are damage resilient and armed with w ...

. The ''Syracusia'' is said to have been the largest ship built in classical antiquity

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ...

. According to Athenaeus, it was capable of carrying 600 people and included garden decorations, a gymnasium and a temple dedicated to the goddess Aphrodite

Aphrodite ( ; grc-gre, Ἀφροδίτη, Aphrodítē; , , ) is an ancient Greek goddess associated with love, lust, beauty, pleasure, passion, and procreation. She was syncretized with the Roman goddess . Aphrodite's major symbols incl ...

among its facilities. Since a ship of this size would leak a considerable amount of water through the hull, Archimedes' screw

The Archimedes screw, also known as the Archimedean screw, hydrodynamic screw, water screw or Egyptian screw, is one of the earliest hydraulic machines. Using Archimedes screws as water pumps (Archimedes screw pump (ASP) or screw pump) dates back ...

was purportedly developed in order to remove the bilge water. Archimedes' machine was a device with a revolving screw-shaped blade inside a cylinder. It was turned by hand, and could also be used to transfer water from a body of water into irrigation canals. Archimedes' screw is still in use today for pumping liquids and granulated solids such as coal and grain. Described in Roman times by Vitruvius, Archimedes' screw may have been an improvement on a screw pump that was used to irrigate the Hanging Gardens of Babylon

The Hanging Gardens of Babylon were one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World listed by Hellenic culture. They were described as a remarkable feat of engineering with an ascending series of tiered gardens containing a wide variety of tre ...

. The world's first seagoing steamship

A steamship, often referred to as a steamer, is a type of steam-powered vessel, typically ocean-faring and seaworthy, that is propelled by one or more steam engines that typically move (turn) propellers or paddlewheels. The first steamship ...

with a screw propeller

A propeller (colloquially often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upo ...

was the SS ''Archimedes'', which was launched in 1839 and named in honor of Archimedes and his work on the screw.

Archimedes' claw

Archimedes is said to have designed aclaw

A claw is a curved, pointed appendage found at the end of a toe or finger in most amniotes (mammals, reptiles, birds). Some invertebrates such as beetles and spiders have somewhat similar fine, hooked structures at the end of the leg or tarsus ...

as a weapon to defend the city of Syracuse. Also known as "the ship shaker", the claw consisted of a crane-like arm from which a large metal grappling hook

A grappling hook or grapnel is a device that typically has multiple hooks (known as ''claws'' or ''flukes'') attached to a rope; it is thrown, dropped, sunk, projected, or fastened directly by hand to where at least one hook may catch and ho ...

was suspended. When the claw was dropped onto an attacking ship the arm would swing upwards, lifting the ship out of the water and possibly sinking it.

There have been modern experiments to test the feasibility of the claw, and in 2005 a television documentary entitled ''Superweapons of the Ancient World'' built a version of the claw and concluded that it was a workable device.

Heat ray

parabolic reflector

A parabolic (or paraboloid or paraboloidal) reflector (or dish or mirror) is a reflective surface used to collect or project energy such as light, sound, or radio waves. Its shape is part of a circular paraboloid, that is, the surface genera ...

to burn ships attacking Syracuse. The 2nd-century author Lucian

Lucian of Samosata, '; la, Lucianus Samosatensis ( 125 – after 180) was a Hellenized Syrian satirist, rhetorician and pamphleteer who is best known for his characteristic tongue-in-cheek style, with which he frequently ridiculed supersti ...

wrote that during the siege of Syracuse (c. 214–212 BC), Archimedes destroyed enemy ships with fire. Centuries later, Anthemius of Tralles

Anthemius of Tralles ( grc-gre, Ἀνθέμιος ὁ Τραλλιανός, Medieval Greek: , ''Anthémios o Trallianós''; – 533 558) was a Greek from Tralles who worked as a geometer and architect in Constantinople, the ca ...

mentions burning-glass

A burning glass or burning lens is a large convex lens that can concentrate the sun's rays onto a small area, heating up the area and thus resulting in ignition of the exposed surface. Burning mirrors achieve a similar effect by using reflecting ...

es as Archimedes' weapon. The device, sometimes called the "Archimedes heat ray", was used to focus sunlight onto approaching ships, causing them to catch fire. In the modern era, similar devices have been constructed and may be referred to as a heliostat

A heliostat (from '' helios'', the Greek word for ''sun'', and ''stat'', as in stationary) is a device that includes a mirror, usually a plane mirror, which turns so as to keep reflecting sunlight toward a predetermined target, compensating ...

or solar furnace.

This purported weapon has been the subject of an ongoing debate about its credibility since the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

. René Descartes

René Descartes ( or ; ; Latinized: Renatus Cartesius; 31 March 1596 – 11 February 1650) was a French philosopher, scientist, and mathematician, widely considered a seminal figure in the emergence of modern philosophy and science. Ma ...

rejected it as false, while modern researchers have attempted to recreate the effect using only the means that would have been available to Archimedes, mostly with negative results. It has been suggested that a large array of highly polished bronze

Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12–12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals (including aluminium, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals, such as phosphorus, or metalloids suc ...

or copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (from la, cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pink ...

shields acting as mirrors could have been employed to focus sunlight onto a ship, but the overall effect would have been blinding, dazzling, or distracting the crew of the ship rather than fire.

Lever

While Archimedes did not invent thelever

A lever is a simple machine consisting of a beam or rigid rod pivoted at a fixed hinge, or '' fulcrum''. A lever is a rigid body capable of rotating on a point on itself. On the basis of the locations of fulcrum, load and effort, the lever is d ...

, he gave a mathematical proof of the principle involved in his work ''On the Equilibrium of Planes

''On the Equilibrium of Planes'' ( grc, Περὶ ἐπιπέδων ἱσορροπιῶν, translit=perí epipédōn isorropiôn) is a treatise by Archimedes in two volumes. The first book contains a proof of the law of the lever and culminates ...

''. Earlier descriptions of the lever are found in the Peripatetic school

The Peripatetic school was a school of philosophy in Ancient Greece. Its teachings derived from its founder, Aristotle (384–322 BC), and ''peripatetic'' is an adjective ascribed to his followers.

The school dates from around 335 BC when Aristo ...

of the followers of Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

, and are sometimes attributed to Archytas

Archytas (; el, Ἀρχύτας; 435/410–360/350 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosopher, mathematician, music theorist, astronomer, statesman, and strategist. He was a scientist of the Pythagorean school and famous for being the reputed found ...

. There are several, often conflicting, reports regarding Archimedes' feats using the lever to lift very heavy objects. Plutarch describes how Archimedes designed block-and-tackle pulley

A pulley is a wheel on an axle or shaft that is designed to support movement and change of direction of a taut cable or belt, or transfer of power between the shaft and cable or belt. In the case of a pulley supported by a frame or shell that ...

systems, allowing sailors to use the principle of lever

A lever is a simple machine consisting of a beam or rigid rod pivoted at a fixed hinge, or '' fulcrum''. A lever is a rigid body capable of rotating on a point on itself. On the basis of the locations of fulcrum, load and effort, the lever is d ...

age to lift objects that would otherwise have been too heavy to move. According to Pappus of Alexandria

Pappus of Alexandria (; grc-gre, Πάππος ὁ Ἀλεξανδρεύς; AD) was one of the last great Greek mathematicians of antiquity known for his ''Synagoge'' (Συναγωγή) or ''Collection'' (), and for Pappus's hexagon theorem i ...

, Archimedes' work on levers caused him to remark: "Give me a place to stand on, and I will move the Earth" ( el, δῶς μοι πᾶ στῶ καὶ τὰν γᾶν κινάσω). Olympiodorus later attributed the same boast to Archimedes' invention of the ''baroulkos'', a kind of windlass

The windlass is an apparatus for moving heavy weights. Typically, a windlass consists of a horizontal cylinder (barrel), which is rotated by the turn of a crank or belt. A winch is affixed to one or both ends, and a cable or rope is wound arou ...

, rather than the lever.

Archimedes has also been credited with improving the power and accuracy of the catapult

A catapult is a ballistic device used to launch a projectile a great distance without the aid of gunpowder or other propellants – particularly various types of ancient and medieval siege engines. A catapult uses the sudden release of stor ...

, and with inventing the odometer

An odometer or odograph is an instrument used for measuring the distance traveled by a vehicle, such as a bicycle or car. The device may be electronic, mechanical, or a combination of the two ( electromechanical). The noun derives from ancient G ...

during the First Punic War

The First Punic War (264–241 BC) was the first of Punic Wars, three wars fought between Roman Republic, Rome and Ancient Carthage, Carthage, the two main powers of the western Mediterranean in the early 3rd century BC. For 23 years ...

. The odometer was described as a cart with a gear mechanism that dropped a ball into a container after each mile traveled.

Astronomical instruments

Archimedes discusses astronomical measurements of the Earth, Sun, and Moon, as well as Aristarchus' heliocentric model of the universe, in the ''Sand-Reckoner''. Without the use of either trigonometry or a table of chords, Archimedes describes the procedure and instrument used to make observations (a straight rod with pegs or grooves), applies correction factors to these measurements, and finally gives the result in the form of upper and lower bounds to account for observational error.Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importanc ...

, quoting Hipparchus, also references Archimedes' solstice observations in the ''Almagest''. This would make Archimedes the first known Greek to have recorded multiple solstice dates and times in successive years.

Cicero's ''De re publica

''De re publica'' (''On the Commonwealth''; see below) is a dialogue on Roman politics by Cicero, written in six books between 54 and 51 BC. The work does not survive in a complete state, and large parts are missing. The surviving sections derive ...

'' portrays a fictional conversation taking place in 129 BC, after the Second Punic War

The Second Punic War (218 to 201 BC) was the second of three wars fought between Carthage and Rome, the two main powers of the western Mediterranean in the 3rd century BC. For 17 years the two states struggled for supremacy, primarily in Ital ...

. General Marcus Claudius Marcellus

Marcus Claudius Marcellus (; 270 – 208 BC), five times elected as consul of the Roman Republic, was an important Roman military leader during the Gallic War of 225 BC and the Second Punic War. Marcellus gained the most prestigious award a Roma ...

is said to have taken back to Rome two mechanisms after capturing Syracuse in 212 BC, which were constructed by Archimedes and which showed the motion of the Sun, Moon and five planets. Cicero also mentions similar mechanisms designed by Thales of Miletus

Thales of Miletus ( ; grc-gre, Θαλῆς; ) was a Greek mathematician, astronomer, statesman, and pre-Socratic philosopher from Miletus in Ionia, Asia Minor. He was one of the Seven Sages of Greece. Many, most notably Aristotle, regarded ...

and Eudoxus of Cnidus

Eudoxus of Cnidus (; grc, Εὔδοξος ὁ Κνίδιος, ''Eúdoxos ho Knídios''; ) was an ancient Greek astronomer, mathematician, scholar, and student of Archytas and Plato. All of his original works are lost, though some fragments are ...

. The dialogue says that Marcellus kept one of the devices as his only personal loot from Syracuse, and donated the other to the Temple of Virtue in Rome. Marcellus' mechanism was demonstrated, according to Cicero, by Gaius Sulpicius Gallus Gaius Sulpicius Gallus or Galus () was a general, statesman and orator of the Roman Republic.

In 169 BC, he served as ''praetor urbanus''.Livy xliii.14

Under Lucius Aemilius Paulus, his intimate friend, he commanded the 2nd legion in the campaign ...

to Lucius Furius Philus Lucius Furius Philus was a Roman statesman who became consul of ancient Rome in 136 BC. He was a member of the Scipionic Circle, and particularly close to Scipio Aemilianus.

As proconsul, his allotted province was Spain. The consul of the previous ...

, who described it thus:

This is a description of a small planetarium

A planetarium ( planetariums or ''planetaria'') is a Theater (structure), theatre built primarily for presenting educational entertainment, educational and entertaining shows about astronomy and the night sky, or for training in celestial navi ...

. Pappus of Alexandria

Pappus of Alexandria (; grc-gre, Πάππος ὁ Ἀλεξανδρεύς; AD) was one of the last great Greek mathematicians of antiquity known for his ''Synagoge'' (Συναγωγή) or ''Collection'' (), and for Pappus's hexagon theorem i ...

reports on a treatise by Archimedes (now lost) dealing with the construction of these mechanisms entitled ''On Sphere-Making''. Modern research in this area has been focused on the Antikythera mechanism

The Antikythera mechanism ( ) is an Ancient Greek hand-powered orrery, described as the oldest example of an analogue computer used to predict astronomical positions and eclipses decades in advance. It could also be used to track the four-y ...

, another device built BC that was probably designed for the same purpose. Constructing mechanisms of this kind would have required a sophisticated knowledge of differential gearing. This was once thought to have been beyond the range of the technology available in ancient times, but the discovery of the Antikythera mechanism in 1902 has confirmed that devices of this kind were known to the ancient Greeks.

Mathematics

While he is often regarded as a designer of mechanical devices, Archimedes also made contributions to the field ofmathematics

Mathematics is an area of knowledge that includes the topics of numbers, formulas and related structures, shapes and the spaces in which they are contained, and quantities and their changes. These topics are represented in modern mathematics ...

. Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for hi ...

wrote that Archimedes "placed his whole affection and ambition in those purer speculations where there can be no reference to the vulgar needs of life", though some scholars believe this may be a mischaracterization.

Method of exhaustion

infinitesimal

In mathematics, an infinitesimal number is a quantity that is closer to zero than any standard real number, but that is not zero. The word ''infinitesimal'' comes from a 17th-century Modern Latin coinage ''infinitesimus'', which originally re ...

s) in a way that is similar to modern integral calculus

In mathematics, an integral assigns numbers to Function (mathematics), functions in a way that describes Displacement (geometry), displacement, area, volume, and other concepts that arise by combining infinitesimal data. The process of finding ...

. Through proof by contradiction (''reductio ad absurdum

In logic, (Latin for "reduction to absurdity"), also known as (Latin for "argument to absurdity") or ''apagogical arguments'', is the form of argument that attempts to establish a claim by showing that the opposite scenario would lead to absu ...

''), he could give answers to problems to an arbitrary degree of accuracy, while specifying the limits within which the answer lay. This technique is known as the method of exhaustion

The method of exhaustion (; ) is a method of finding the area of a shape by inscribing inside it a sequence of polygons whose areas converge to the area of the containing shape. If the sequence is correctly constructed, the difference in are ...

, and he employed it to approximate the areas of figures and the value of π.

In ''Measurement of a Circle

''Measurement of a Circle'' or ''Dimension of the Circle'' (Greek: , ''Kuklou metrēsis'') is a treatise that consists of three propositions by Archimedes, ca. 250 BCE. The treatise is only a fraction of what was a longer work.

Propositions

Prop ...

'', he did this by drawing a larger regular hexagon

In geometry, a hexagon (from Ancient Greek, Greek , , meaning "six", and , , meaning "corner, angle") is a six-sided polygon. The total of the internal angles of any simple polygon, simple (non-self-intersecting) hexagon is 720°.

Regular hexa ...

outside a circle

A circle is a shape consisting of all points in a plane that are at a given distance from a given point, the centre. Equivalently, it is the curve traced out by a point that moves in a plane so that its distance from a given point is cons ...

then a smaller regular hexagon inside the circle, and progressively doubling the number of sides of each regular polygon

In Euclidean geometry, a regular polygon is a polygon that is direct equiangular (all angles are equal in measure) and equilateral (all sides have the same length). Regular polygons may be either convex, star or skew. In the limit, a sequence ...

, calculating the length of a side of each polygon at each step. As the number of sides increases, it becomes a more accurate approximation of a circle. After four such steps, when the polygons had 96 sides each, he was able to determine that the value of π lay between 3 (approx. 3.1429) and 3 (approx. 3.1408), consistent with its actual value of approximately 3.1416. He also proved that the area of a circle

In geometry, the area enclosed by a circle of radius is . Here the Greek letter represents the constant ratio of the circumference of any circle to its diameter, approximately equal to 3.14159.

One method of deriving this formula, which ori ...

was equal to π multiplied by the square

In Euclidean geometry, a square is a regular quadrilateral, which means that it has four equal sides and four equal angles (90- degree angles, π/2 radian angles, or right angles). It can also be defined as a rectangle with two equal-length a ...

of the radius

In classical geometry, a radius (plural, : radii) of a circle or sphere is any of the line segments from its Centre (geometry), center to its perimeter, and in more modern usage, it is also their length. The name comes from the latin ''radius'', ...

of the circle ().

Archimedean property

In ''On the Sphere and Cylinder

''On the Sphere and Cylinder'' ( el, Περὶ σφαίρας καὶ κυλίνδρου) is a work that was published by Archimedes in two volumes c. 225 BCE. It most notably details how to find the surface area of a sphere and the volume of t ...

'', Archimedes postulates that any magnitude when added to itself enough times will exceed any given magnitude. Today this is known as the Archimedean property

In abstract algebra and analysis, the Archimedean property, named after the ancient Greek mathematician Archimedes of Syracuse, is a property held by some algebraic structures, such as ordered or normed groups, and fields.

The property, typica ...

of real numbers.

Archimedes gives the value of the square root

In mathematics, a square root of a number is a number such that ; in other words, a number whose '' square'' (the result of multiplying the number by itself, or ⋅ ) is . For example, 4 and −4 are square roots of 16, because .

...

of 3 as lying between (approximately 1.7320261) and (approximately 1.7320512) in ''Measurement of a Circle''. The actual value is approximately 1.7320508, making this a very accurate estimate. He introduced this result without offering any explanation of how he had obtained it. This aspect of the work of Archimedes caused John Wallis

John Wallis (; la, Wallisius; ) was an English clergyman and mathematician who is given partial credit for the development of infinitesimal calculus. Between 1643 and 1689 he served as chief cryptographer for Parliament and, later, the royal ...

to remark that he was: "as it were of set purpose to have covered up the traces of his investigation as if he had grudged posterity the secret of his method of inquiry while he wished to extort from them assent to his results." It is possible that he used an iterative

Iteration is the repetition of a process in order to generate a (possibly unbounded) sequence of outcomes. Each repetition of the process is a single iteration, and the outcome of each iteration is then the starting point of the next iteration. ...

procedure to calculate these values.

The infinite series

Quadrature of the Parabola

''Quadrature of the Parabola'' ( el, Τετραγωνισμὸς παραβολῆς) is a treatise on geometry, written by Archimedes in the 3rd century BC and addressed to his Alexandrian acquaintance Dositheus. It contains 24 propositions rega ...

'', Archimedes proved that the area enclosed by a parabola

In mathematics, a parabola is a plane curve which is mirror-symmetrical and is approximately U-shaped. It fits several superficially different mathematical descriptions, which can all be proved to define exactly the same curves.

One descri ...

and a straight line is times the area of a corresponding inscribed triangle

A triangle is a polygon with three edges and three vertices. It is one of the basic shapes in geometry. A triangle with vertices ''A'', ''B'', and ''C'' is denoted \triangle ABC.

In Euclidean geometry, any three points, when non- colline ...

as shown in the figure at right. He expressed the solution to the problem as an infinite

Infinite may refer to:

Mathematics

* Infinite set, a set that is not a finite set

*Infinity, an abstract concept describing something without any limit

Music

*Infinite (group), a South Korean boy band

*''Infinite'' (EP), debut EP of American m ...

geometric series

In mathematics, a geometric series is the sum of an infinite number of terms that have a constant ratio between successive terms. For example, the series

:\frac \,+\, \frac \,+\, \frac \,+\, \frac \,+\, \cdots

is geometric, because each suc ...

with the common ratio :

:

If the first term in this series is the area of the triangle, then the second is the sum of the areas of two triangles whose bases are the two smaller secant line

Secant is a term in mathematics derived from the Latin ''secare'' ("to cut"). It may refer to:

* a secant line, in geometry

* the secant variety, in algebraic geometry

* secant (trigonometry) (Latin: secans), the multiplicative inverse (or recipr ...

s, and whose third vertex is where the line that is parallel to the parabola's axis and that passes through the midpoint of the base intersects the parabola, and so on. This proof uses a variation of the series which sums to .

Myriad of myriads

In ''The Sand Reckoner

''The Sand Reckoner'' ( el, Ψαμμίτης, ''Psammites'') is a work by Archimedes, an Ancient Greek mathematician of the 3rd century BC, in which he set out to determine an upper bound for the number of grains of sand that fit into the unive ...

'', Archimedes set out to calculate the number of grains of sand that the universe could contain. In doing so, he challenged the notion that the number of grains of sand was too large to be counted. He wrote:There are some, King Gelo (Gelo II, son of Hiero II), who think that the number of the sand is infinite in multitude; and I mean by the sand not only that which exists about Syracuse and the rest of Sicily but also that which is found in every region whether inhabited or uninhabited.To solve the problem, Archimedes devised a system of counting based on the

myriad

A myriad (from Ancient Greek grc, μυριάς, translit=myrias, label=none) is technically the number 10,000 (ten thousand); in that sense, the term is used in English almost exclusively for literal translations from Greek, Latin or Sinospher ...

. The word itself derives from the Greek , for the number 10,000. He proposed a number system using powers of a myriad of myriads (100 million, i.e., 10,000 x 10,000) and concluded that the number of grains of sand required to fill the universe would be 8 vigintillion, or 8.

Writings

The works of Archimedes were written in

The works of Archimedes were written in Doric Greek

Doric or Dorian ( grc, Δωρισμός, Dōrismós), also known as West Greek, was a group of Ancient Greek dialects; its varieties are divided into the Doric proper and Northwest Doric subgroups. Doric was spoken in a vast area, that includ ...

, the dialect of ancient Syracuse. Many written works by Archimedes have not survived or are only extant in heavily edited fragments; at least seven of his treatises are known to have existed due to references made by other authors. Pappus of Alexandria

Pappus of Alexandria (; grc-gre, Πάππος ὁ Ἀλεξανδρεύς; AD) was one of the last great Greek mathematicians of antiquity known for his ''Synagoge'' (Συναγωγή) or ''Collection'' (), and for Pappus's hexagon theorem i ...

mentions ''On Sphere-Making'' and another work on polyhedra

In geometry, a polyhedron (plural polyhedra or polyhedrons; ) is a three-dimensional shape with flat polygonal faces, straight edges and sharp corners or vertices.

A convex polyhedron is the convex hull of finitely many points, not all on ...

, while Theon of Alexandria

Theon of Alexandria (; grc, Θέων ὁ Ἀλεξανδρεύς; 335 – c. 405) was a Greek scholar and mathematician who lived in Alexandria, Egypt. He edited and arranged Euclid's '' Elements'' and wrote commentaries on w ...

quotes a remark about refraction

In physics, refraction is the redirection of a wave as it passes from one medium to another. The redirection can be caused by the wave's change in speed or by a change in the medium. Refraction of light is the most commonly observed phenomen ...

from the ''Catoptrica''.The treatises by Archimedes known to exist only through references in the works of other authors are: ''On Sphere-Making'' and a work on polyhedra

In geometry, a polyhedron (plural polyhedra or polyhedrons; ) is a three-dimensional shape with flat polygonal faces, straight edges and sharp corners or vertices.

A convex polyhedron is the convex hull of finitely many points, not all on ...

mentioned by Pappus of Alexandria

Pappus of Alexandria (; grc-gre, Πάππος ὁ Ἀλεξανδρεύς; AD) was one of the last great Greek mathematicians of antiquity known for his ''Synagoge'' (Συναγωγή) or ''Collection'' (), and for Pappus's hexagon theorem i ...

; ''Catoptrica'', a work on optics mentioned by Theon of Alexandria

Theon of Alexandria (; grc, Θέων ὁ Ἀλεξανδρεύς; 335 – c. 405) was a Greek scholar and mathematician who lived in Alexandria, Egypt. He edited and arranged Euclid's '' Elements'' and wrote commentaries on w ...

; ''Principles'', addressed to Zeuxippus and explaining the number system used in ''The Sand Reckoner

''The Sand Reckoner'' ( el, Ψαμμίτης, ''Psammites'') is a work by Archimedes, an Ancient Greek mathematician of the 3rd century BC, in which he set out to determine an upper bound for the number of grains of sand that fit into the unive ...

''; ''On Balances and Levers''; ''On Centers of Gravity''; ''On the Calendar''.

Archimedes made his work known through correspondence with the mathematicians in Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

. The writings of Archimedes were first collected by the Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

Greek architect Isidore of Miletus

Isidore of Miletus ( el, Ἰσίδωρος ὁ Μιλήσιος; Medieval Greek pronunciation: ; la, Isidorus Miletus) was one of the two main Byzantine Greek architects (Anthemius of Tralles was the other) that Emperor Justinian I commissioned ...

(c. 530 AD), while commentaries on the works of Archimedes written by Eutocius

Eutocius of Ascalon (; el, Εὐτόκιος ὁ Ἀσκαλωνίτης; 480s – 520s) was a Palestinian-Greek mathematician who wrote commentaries on several Archimedean treatises and on the Apollonian ''Conics''.

Life and work

Little is ...

in the sixth century AD helped to bring his work a wider audience. Archimedes' work was translated into Arabic by Thābit ibn Qurra (836–901 AD), and into Latin via Arabic by Gerard of Cremona

Gerard of Cremona (Latin: ''Gerardus Cremonensis''; c. 1114 – 1187) was an Italian translator of scientific books from Arabic into Latin. He worked in Toledo, Kingdom of Castile and obtained the Arabic books in the libraries at Toledo. Some of ...

(c. 1114–1187). Direct Greek to Latin translations were later done by William of Moerbeke

William of Moerbeke, O.P. ( nl, Willem van Moerbeke; la, Guillelmus de Morbeka; 1215–35 – 1286), was a prolific medieval translator of philosophical, medical, and scientific texts from Greek language into Latin, enabled by the period ...

(c. 1215–1286) and Iacobus Cremonensis (c. 1400–1453).

During the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

, the ''Editio princeps In classical scholarship, the ''editio princeps'' (plural: ''editiones principes'') of a work is the first printed edition of the work, that previously had existed only in manuscripts, which could be circulated only after being copied by hand.

For ...

'' (First Edition) was published in Basel

, french: link=no, Bâlois(e), it, Basilese

, neighboring_municipalities= Allschwil (BL), Hégenheim (FR-68), Binningen (BL), Birsfelden (BL), Bottmingen (BL), Huningue (FR-68), Münchenstein (BL), Muttenz (BL), Reinach (BL), Riehen (B ...

in 1544 by Johann Herwagen with the works of Archimedes in Greek and Latin.

Surviving works

The following are ordered chronologically based on new terminological and historical criteria set by Knorr (1978) and Sato (1986).''Measurement of a Circle''

This is a short work consisting of three propositions. It is written in the form of a correspondence with Dositheus of Pelusium, who was a student ofConon of Samos

Conon of Samos ( el, Κόνων ὁ Σάμιος, ''Konōn ho Samios''; c. 280 – c. 220 BC) was a Greek astronomer and mathematician. He is primarily remembered for naming the constellation Coma Berenices.

Life and work

Conon was born on Sam ...

. In Proposition II, Archimedes gives an approximation

An approximation is anything that is intentionally similar but not exactly equal to something else.

Etymology and usage

The word ''approximation'' is derived from Latin ''approximatus'', from ''proximus'' meaning ''very near'' and the prefix ' ...

of the value of pi (), showing that it is greater than and less than .

''The Sand Reckoner''

In this treatise, also known as ''Psammites'', Archimedes counts the number of grains of sand that will fit inside the universe. This book mentions theheliocentric

Heliocentrism (also known as the Heliocentric model) is the astronomical model in which the Earth and planets revolve around the Sun at the center of the universe. Historically, heliocentrism was opposed to geocentrism, which placed the Earth ...

theory of the solar system

The Solar System Capitalization of the name varies. The International Astronomical Union, the authoritative body regarding astronomical nomenclature, specifies capitalizing the names of all individual astronomical objects but uses mixed "Solar ...

proposed by Aristarchus of Samos

Aristarchus of Samos (; grc-gre, Ἀρίσταρχος ὁ Σάμιος, ''Aristarkhos ho Samios''; ) was an ancient Greek astronomer and mathematician who presented the first known heliocentric model that placed the Sun at the center of the ...

, as well as contemporary ideas about the size of the Earth and the distance between various celestial bodies

An astronomical object, celestial object, stellar object or heavenly body is a naturally occurring physical entity, association, or structure that exists in the observable universe. In astronomy, the terms ''object'' and ''body'' are often us ...

. By using a system of numbers based on powers of the myriad

A myriad (from Ancient Greek grc, μυριάς, translit=myrias, label=none) is technically the number 10,000 (ten thousand); in that sense, the term is used in English almost exclusively for literal translations from Greek, Latin or Sinospher ...

, Archimedes concludes that the number of grains of sand required to fill the universe is 8 in modern notation. The introductory letter states that Archimedes' father was an astronomer named Phidias. ''The Sand Reckoner'' is the only surviving work in which Archimedes discusses his views on astronomy.

''On the Equilibrium of Planes''

There are two books to ''On the Equilibrium of Planes'': the first contains sevenpostulates

An axiom, postulate, or assumption is a statement that is taken to be true, to serve as a premise or starting point for further reasoning and arguments. The word comes from the Ancient Greek word (), meaning 'that which is thought worthy or f ...

and fifteen proposition

In logic and linguistics, a proposition is the meaning of a declarative sentence. In philosophy, " meaning" is understood to be a non-linguistic entity which is shared by all sentences with the same meaning. Equivalently, a proposition is the no ...

s, while the second book contains ten propositions. In the first work, Archimedes proves the ''Law of the lever

A lever is a simple machine consisting of a beam or rigid rod pivoted at a fixed hinge, or ''fulcrum''. A lever is a rigid body capable of rotating on a point on itself. On the basis of the locations of fulcrum, load and effort, the lever is div ...

'', which states that:

Archimedes uses the principles derived to calculate the areas and centers of gravity of various geometric figures including triangle

A triangle is a polygon with three edges and three vertices. It is one of the basic shapes in geometry. A triangle with vertices ''A'', ''B'', and ''C'' is denoted \triangle ABC.

In Euclidean geometry, any three points, when non- colline ...

s, parallelogram

In Euclidean geometry, a parallelogram is a simple (non- self-intersecting) quadrilateral with two pairs of parallel sides. The opposite or facing sides of a parallelogram are of equal length and the opposite angles of a parallelogram are of eq ...

s and parabola

In mathematics, a parabola is a plane curve which is mirror-symmetrical and is approximately U-shaped. It fits several superficially different mathematical descriptions, which can all be proved to define exactly the same curves.

One descri ...

s.

''Quadrature of the Parabola''

In this work of 24 propositions addressed to Dositheus, Archimedes proves by two methods that the area enclosed by aparabola

In mathematics, a parabola is a plane curve which is mirror-symmetrical and is approximately U-shaped. It fits several superficially different mathematical descriptions, which can all be proved to define exactly the same curves.

One descri ...

and a straight line is 4/3 times the area of a triangle

A triangle is a polygon with three edges and three vertices. It is one of the basic shapes in geometry. A triangle with vertices ''A'', ''B'', and ''C'' is denoted \triangle ABC.

In Euclidean geometry, any three points, when non- colline ...

with equal base and height. He achieves this by calculating the value of a geometric series

In mathematics, a geometric series is the sum of an infinite number of terms that have a constant ratio between successive terms. For example, the series

:\frac \,+\, \frac \,+\, \frac \,+\, \frac \,+\, \cdots

is geometric, because each suc ...

that sums to infinity with the ratio

In mathematics, a ratio shows how many times one number contains another. For example, if there are eight oranges and six lemons in a bowl of fruit, then the ratio of oranges to lemons is eight to six (that is, 8:6, which is equivalent to the ...

.

''On the Sphere and Cylinder''

sphere

A sphere () is a geometrical object that is a three-dimensional analogue to a two-dimensional circle. A sphere is the set of points that are all at the same distance from a given point in three-dimensional space.. That given point is the c ...

and a circumscribed cylinder

A cylinder (from ) has traditionally been a three-dimensional solid, one of the most basic of curvilinear geometric shapes. In elementary geometry, it is considered a prism with a circle as its base.

A cylinder may also be defined as an ...

of the same height and diameter

In geometry, a diameter of a circle is any straight line segment that passes through the center of the circle and whose endpoints lie on the circle. It can also be defined as the longest chord of the circle. Both definitions are also valid f ...

. The volume is 3 for the sphere, and 23 for the cylinder. The surface area is 42 for the sphere, and 62 for the cylinder (including its two bases), where is the radius of the sphere and cylinder. The sphere has a volume that of the circumscribed cylinder. Similarly, the sphere has an area that of the cylinder (including the bases).

''On Spirals''

This work of 28 propositions is also addressed to Dositheus. The treatise defines what is now called theArchimedean spiral

The Archimedean spiral (also known as the arithmetic spiral) is a spiral named after the 3rd-century BC Greek mathematician Archimedes. It is the locus corresponding to the locations over time of a point moving away from a fixed point with a ...

. It is the locus

Locus (plural loci) is Latin for "place". It may refer to:

Entertainment

* Locus (comics), a Marvel Comics mutant villainess, a member of the Mutant Liberation Front

* ''Locus'' (magazine), science fiction and fantasy magazine

** ''Locus Award' ...

of points corresponding to the locations over time of a point moving away from a fixed point with a constant speed along a line which rotates with constant angular velocity

In physics, angular velocity or rotational velocity ( or ), also known as angular frequency vector,(UP1) is a pseudovector representation of how fast the angular position or orientation of an object changes with time (i.e. how quickly an object ...

. Equivalently, in polar coordinates

In mathematics, the polar coordinate system is a two-dimensional coordinate system in which each point on a plane is determined by a distance from a reference point and an angle from a reference direction. The reference point (analogous to th ...

(, ) it can be described by the equation with real number

In mathematics, a real number is a number that can be used to measure a ''continuous'' one-dimensional quantity such as a distance, duration or temperature. Here, ''continuous'' means that values can have arbitrarily small variations. Every ...

s and .

This is an early example of a mechanical curve (a curve traced by a moving point) considered by a Greek mathematician.

''On Conoids and Spheroids''

This is a work in 32 propositions addressed to Dositheus. In this treatise Archimedes calculates the areas and volumes ofsections

Section, Sectioning or Sectioned may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media

* Section (music), a complete, but not independent, musical idea

* Section (typography), a subdivision, especially of a chapter, in books and documents

** Section sig ...

of cones

A cone is a three-dimensional geometric shape that tapers smoothly from a flat base (frequently, though not necessarily, circular) to a point called the apex or vertex.

A cone is formed by a set of line segments, half-lines, or lines conn ...

, spheres, and paraboloids.

''On Floating Bodies''

In the first part of this two-volume treatise, Archimedes spells out the law of equilibrium of fluids and proves that water will adopt a spherical form around a center of gravity. This may have been an attempt at explaining the theory of contemporary Greek astronomers such asEratosthenes

Eratosthenes of Cyrene (; grc-gre, Ἐρατοσθένης ; – ) was a Greek polymath: a mathematician, geographer, poet, astronomer, and music theorist. He was a man of learning, becoming the chief librarian at the Library of Alexandr ...

that the Earth is round. The fluids described by Archimedes are not since he assumes the existence of a point towards which all things fall in order to derive the spherical shape. Archimedes' principle of buoyancy is given in this work, stated as follows:Any body wholly or partially immersed in fluid experiences an upthrust equal to, but opposite in sense to, the weight of the fluid displaced.In the second part, he calculates the equilibrium positions of sections of paraboloids. This was probably an idealization of the shapes of ships' hulls. Some of his sections float with the base under water and the summit above water, similar to the way that icebergs float.

''Ostomachion''

dissection puzzle

A dissection puzzle, also called a transformation puzzle or ''Richter Puzzle'', is a tiling puzzle where a set of pieces can be assembled in different ways to produce two or more distinct geometric shapes. The creation of new dissection puzzles ...

similar to a Tangram

The tangram () is a dissection puzzle consisting of seven flat polygons, called ''tans'', which are put together to form shapes. The objective is to replicate a pattern (given only an outline) generally found in a puzzle book using all seven pi ...

, and the treatise describing it was found in more complete form in the ''Archimedes Palimpsest

The Archimedes Palimpsest is a parchment codex palimpsest, originally a Byzantine Greek copy of a compilation of Archimedes and other authors. It contains two works of Archimedes that were thought to have been lost (the '' Ostomachion'' and ...

''. Archimedes calculates the areas of the 14 pieces which can be assembled to form a square

In Euclidean geometry, a square is a regular quadrilateral, which means that it has four equal sides and four equal angles (90- degree angles, π/2 radian angles, or right angles). It can also be defined as a rectangle with two equal-length a ...

. Reviel Netz

Reviel Netz (born January 2, 1968) is an Israeli scholar of the history of pre-modern mathematics, who is currently a professor of classics and of philosophy at Stanford University.

Life and work

Netz was born January 2, 1968, in Tel Aviv, Isra ...

of Stanford University

Stanford University, officially Leland Stanford Junior University, is a private research university in Stanford, California. The campus occupies , among the largest in the United States, and enrolls over 17,000 students. Stanford is conside ...